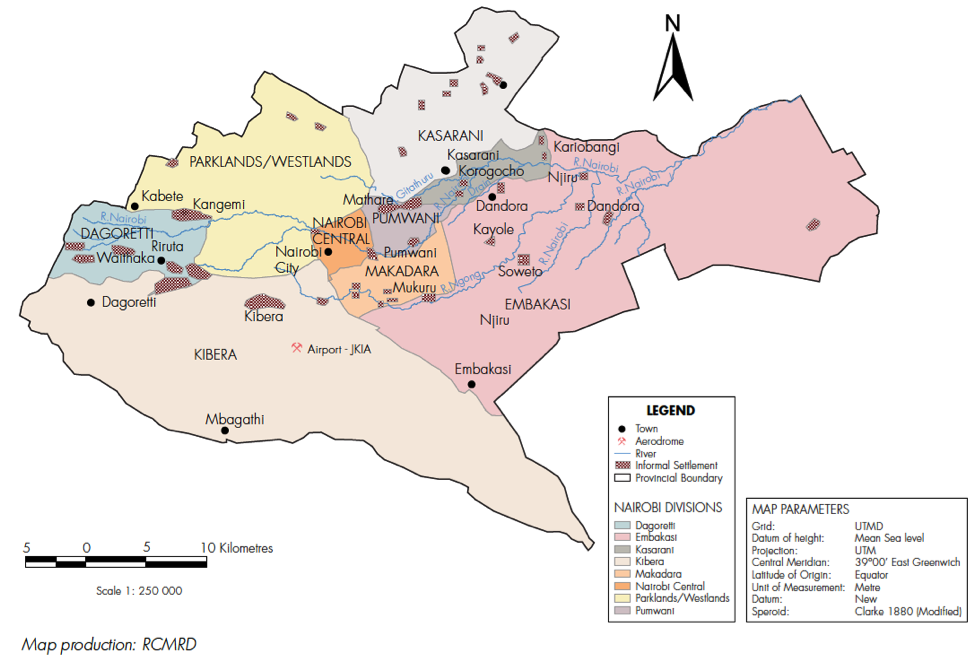

Sometimes it is only a short way from paradise to hell. The journey from Gigiri to Korogocho takes less than half an hour. Gigiri is one of the wealthiest districts of Nairobi. The United Nations has its headquarters here, the US Embassy is here, entrenched behind barbed wire and high walls. Jacaranda trees blossom in bright purple, the residences of the diplomats are surrounded by lush green, cultivated by a swarm of employees.

During my research stay in Nairobi, I drove from beautiful Girigi where I had an interview with UNICEF to the informal settlement Korogocho. The houses once built in Korogocho by the World Bank intending to provide cheap housing for the poorest people give the district a ‘better’ look than the corrugated iron huts of Kibera, Nairobi’s most famous informal settlement. But even in Korogocho, there are no paved streets and for most people, neither water nor electricity. And then there is Dandora, the garbage dumpsite, one of the most tremendous waste dumps in Africa. Have a look at the following video illustrating the dimension of Dandora dumpsite.

The view of Dandora dumpsite in Korogocho was a special event for me. In the valley basin, it glittered among the clouds of smoke of burning garbage. Goats and chickens scratched between plastic bags and rubbish. The few trees that stood between the dumps looked like mockery, a reminder of a more beautiful, greener world that has nothing to do with the reality in Korogocho.

With sticks and poles, hundreds of people, children and adults, poked at the garbage. They ignored the muddy, rotten ground in which they sank ankle-deep with their plastic sandals, the burning, acrid smoke that penetrated their eyes, nose and mouth, that made them dizzy after a short time.

The ‘garbage people’ of Korogocho can’t pay attention to the smoke or the dirt, because for them it’s about their livelihood, about everything that can still be recycled and sold.

About 2000 tons of waste are transported to Dandora every day. This garbage of people from Nairobi’s more prosperous districts is both a livelihood and a curse. Residents of Korogocho live on the garbage, and they die of it, of the poison that is everywhere in air, water, and ground. Many children have chronic respiratory diseases, suffer from circulatory problems and have difficulty concentrating. The United Nations Environment Programme examined several hundred children in the area around Dandora. Half of the children had lead concentrations in their blood that were far above the international limits. Almost half of the children and adolescents examined suffered from respiratory diseases such as chronic bronchitis and asthma.

The soil samples taken in Dandora also showed alarming results. Almost half of them revealed heavy metal concentrations ten times higher than the permissible limits. The heavy metal cadmium, which, in too high levels, damages the organs and can lead to kidney failure and cancer, was measured at the soil surface in Dandora in 50-fold concentrations.

This is all the truer given environmental conditions that are hazardous to health. According to estimates by the World Health Organization (WHO), these risks are responsible for the death of 4.7 million people every year. In developing countries, one in four deaths is attributable such environmental conditions.

No one is as good at recycling as the urban poor. Everything is reused somehow. Reuse – a topic we will discuss later in the blog in the form of circular economies. But reuse must not mean that the lives of the poorest and their families are put at risk. With proper waste management, thousands of jobs could be created for residents of Nairobi’s informal settlements – jobs that can preserve human dignity and health. This is also about human rights and social justice. The lives of nearly a million people are at stake – and the people here are already poor and disadvantaged.

646 words

VISUAL REFERENCES

Featured Image: Kamau, R. (2017). Nairobi’s Dandora Dumpsite. Retrieved from http://nairobiwire.com/2017/11/what-sonko-plans-to-do-about-the-dandora-dump-site.html

The Conversation (2017). Nairobi’s Dandora Dumpsite. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/it-will-take-more-than-good-intentions-to-clear-nairobis-garbage-mountains-88421